Monologues in the Dark

Why men are finding themselves in broken characters — and what it means to be seen in silence.

There’s a certain kind of man who watches a film and walks away quietly haunted — less by the plot, and more by the character who seemed to be speaking his internal language out loud. These are the “literally me” characters: the brooding loner, the detached genius, the wandering antihero. Not aspirational figures, necessarily — but reflections. Mirrors. They don’t show who men want to be; they show how many already feel.

This identification goes deeper than aesthetics or edge. It’s not just about violence, stoicism, or clever dialogue. It’s about recognition. A sense that someone, somewhere, understood the numbness. The isolation. The questions that won’t stop circling in the middle of the night. These characters are vessels — vulnerable, chaotic, often broken — and through them, many men can finally confront what they often struggle to express aloud: pain, disconnection, identity. For me, that mirror was Theodore Twombly in Her.

After a breakup in 2022 that left me unraveling in quiet ways, I found myself rewatching scenes of him wandering through pastel cityscapes, talking softly to a voice that wasn’t real. There was a loneliness there that felt familiar — not performative sadness, but that hollow ache where connection used to live. Theodore wasn’t some larger than life figure. He was just… trying. Trying to understand himself. Trying to feel less alone. And that’s what made him hit so hard.

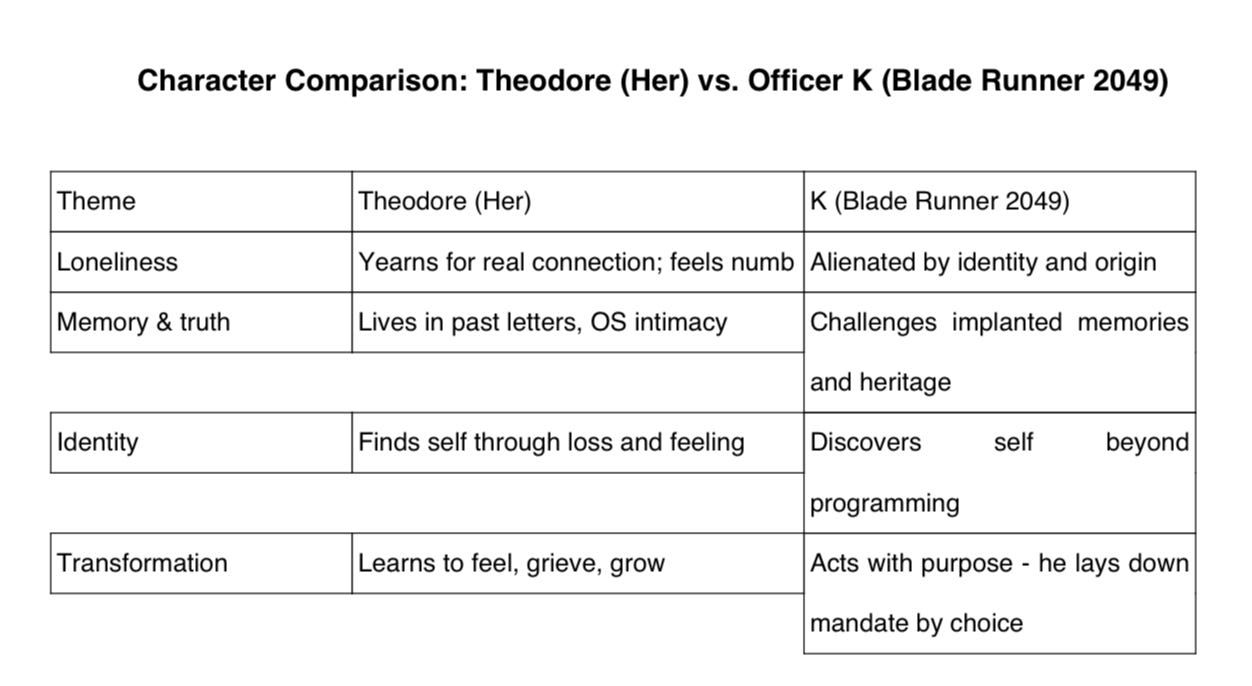

This piece is about that feeling — why men find such powerful resonance in these kinds of characters, and what that says about masculinity, alienation, and the search for meaning. We’ll look at figures like Theodore, Officer K (Blade Runner 2049), Dexter Morgan, Elliot Alderson, Batman, and Johan Liebert. We’ll trace their philosophies, their contradictions, and the reasons men claim them — not just on forums or TikTok, but in private, unspoken ways. At the core of it all is a simple truth: the world doesn’t often give men space to be soft, introspective, or lost. But fiction does. And in these characters, we find a permission slip — maybe even a map.

Soft Solitude & Synth Souls

In Her, Theodore Twombly isn’t a superhero — he’s a blender of nuance, aching for connection in a world that has grown too soft, too polished, too busy for genuine feeling. In his soft pastel apartment and neat, bustling city, he occupies a disquieting void. His love story begins when he buys an operating system — one that evolves from assistant to soulmate, and eventually, an expansion of his own heart. That’s where it clicks for many men: Theodore doesn’t need superpowers or swagger — he needs permission to feel.

Why Theodore resonates:

Emotional transparency: He grieves on camera, drafts heartfelt letters, laughs, cries, moves on. He’s tangible.

Feeling known yet unseen: Theodore’s voice-over narration is confession — it’s the inner monologue many of us suppress.

Quiet doing: No grand gestures. Vulnerability is radical enough.

When I was fresh out of my own relationship, I found myself visiting Theodore’s city. I felt his solitude. I shared his fear of intimacy and his craving for authenticity. I saw how someone could walk through multitudes of connection — every interaction intimate and hollow at once. In his emotional honesty, I found encouragement to acknowledge my own pain, without pretending it didn’t matter. Theodore offers existential permission: it’s okay to feel. And in Her, the OS shutting down at the end isn’t a tragedy — it’s an evolution. He’s forced forward into grief and growth. That’s a lesson.

Enter Officer K in Blade Runner 2049: a replicant whose memories are programmed, whose life feels manufactured, and whose purpose is manufactured too. He works a sterile world of glaciers and neon decay, hunting devices that threaten society’s fragile balance. But he’s far more than a machine. K stumbles across the possibility that he might be the first child born of replicant and human. The weight of that possibility — the weight of genuine choice — shakes him.

Why Officer K resonates:

Existential search: He’s a question mark asking himself why he exists.

Memory and identity: He wrestles with what’s real. What makes a soul when even memories can be implanted?

Quiet steel: Stoic and dutiful, yet capable of tenderness, grief, loyalty.

Many men feel like K — circling childhood scars, not knowing their origins, trying to find a sense of meaning in systems built for them. His journey isn’t physical; it’s metaphysical. His realisation that he might not be special shatters him — but also gives him agency: he could choose how to live from that point on, however small that impact. Sometimes small things matter more than grand gestures.

Shared themes: longing & becoming

Both characters speak to men who haven’t been taught to express vulnerability. Theodore shows us the brave ache of opening up; K carries the burden of being more than what he was made to be, forging purpose from the programming.

Philosophical framework

Theodore as an emotional existentialist He embodies the journey from numbness to feeling. His journaled letters become confessions. His OS connection isn’t hollow — it’s a step toward understanding himself within connection’s fragile branches. In a sense, he answers a philosophical question: Is living enough if it doesn’t feel like living?

K as an ontological realiser. Borrowing from Jean-Paul Sartre: existence precedes essence. K exists first, then chooses. His redefinition of purpose, born from a crisis of identity, aligns with existential freedom. His final act—taking care of Deckard — is an act of ethical being, despite everything telling him he shouldn’t care.

Why men say “literally me”

Not extra, just recognisable

No supernatural power, no showy rebellion — just struggle, patience, longing.Existence affirmed through loss

Theodore and K both find themselves through endings — relationship death, existential death.Softness isn’t weakness

The tears, the doubt, the sleepless mourning — all signs of being deeply alive.Hope in uncertainty

The OS shuts down. Memories unroot. Neither ends with triumph — but both discover something essential: feelings matter.

Fractured Selves & Controlled Chaos

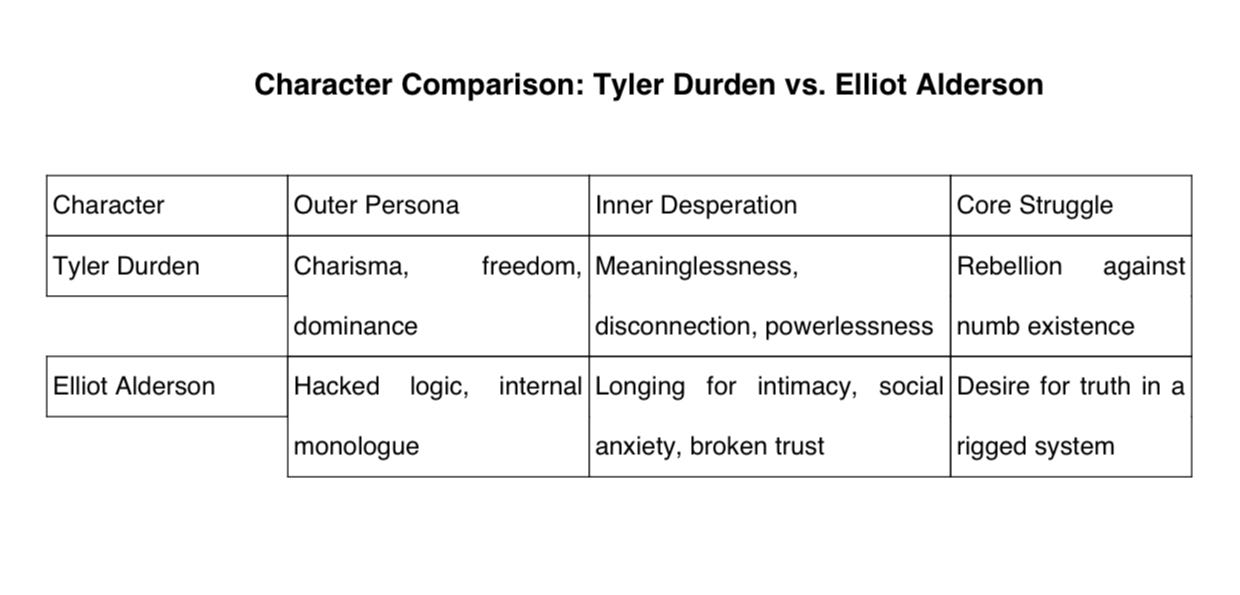

If Theodore and K are portraits of quiet grief, Tyler Durden and Elliot Alderson are the scream behind the silence. Their stories aren’t about healing but rupture. Both represent an eruption of internal chaos — a tearing away from the mask of societal performance. That’s what draws men to them. Not their methods, but their madness. Not the violence, but the desperation behind it.

Tyler Durden: Controlled demolition of identity

At first glance, Tyler Durden seems like everything modern men are told they should be: ripped, confident, unfazed, magnetic. But as Fight Club unravels, we realise he’s not a model — he’s a warning. He isn’t real. He’s the narrator’s suppressed hunger for purpose, unbound by civility. Tyler is the violent byproduct of trying to repress every tender, uncertain, aimless part of oneself.

Men resonate with Tyler not because they want to destroy the world, but because they relate to the feeling that the world already destroyed something in them — and Tyler promises a reclamation. A return to grit. To primal feeling. To intensity in a culture that medicates emotion and markets identity.

“It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

The line is romantic in its nihilism. But it also captures a shared fear: that life has become so curated, so performative, that authenticity can only be found in collapse. Tyler appeals to men who are exhausted by performance — by being soft when they want to scream, by being providers when they feel empty, by being polite in a world that feels indifferent to their quiet suffering.

Elliot Alderson: Digital ghost, analog ache

Where Tyler is bombastic, Elliot is hushed. In Mr. Robot, he is not chasing power — he’s trying to make sense of a system that has already made a mockery of truth. A cybersecurity engineer by day, vigilante hacker by night, Elliot is swallowed by paranoia, isolation, and a fractured psyche. He doesn’t want to burn the world. He wants to know if anyone sees him inside it.

He speaks directly to viewers in voice-over — a device that mimics how many men interact with their own minds: constantly narrating, questioning, replaying. He suffers from dissociative identity disorder, with Mr. Robot — his Tyler-esque alter — guiding him toward revolution.

But Elliot’s story isn’t about the revolution. It’s about why he needed to create another self in the first place.

He’s lonely. Terrified. Lost. And in that, he’s “literally me” to a generation of men drowning in disconnection and overstimulation. Unlike Tyler, Elliot doesn’t celebrate chaos. He mourns it. Every line of code he writes is a cry for clarity.

The Split Identity: Projection vs. Protection

Both characters are illusions — defensive shells. Tyler is who the Narrator wishes he could be; Mr. Robot is who Elliot needs to survive. They’re both fantasies, born of fractured realities.

Why Men Say “Literally Me”

Alienation

Both Tyler and Elliot are disconnected from modern life. Their rejection of societal roles mirrors a generation feeling left behind by progress that doesn’t feed the soul.Unfiltered emotion

Tyler screams. Elliot spirals. Neither apologises. They give voice to the parts men feel they must suppress.Duality

These characters aren’t whole. They’re cracked mirrors — masculinity split between dominance and despair, rage and remorse. And it’s in that fracture that men see themselves most clearly.Purpose through disruption

Whether it’s Project Mayhem or fsociety, both characters attempt to rewrite the system, not to be heroes — but to make their pain mean something.

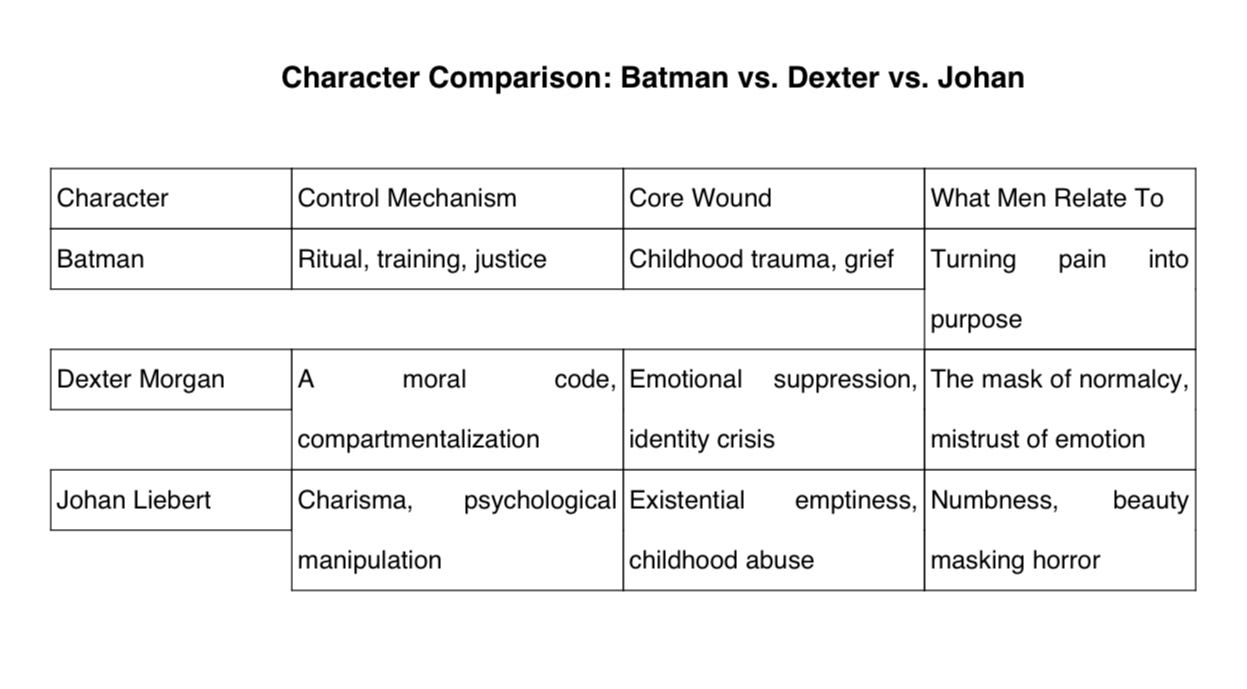

Cold Faces, Heavy Shadows

Not all “literally me” characters bleed on the surface. Some bleed inward — quietly, methodically, and with terrifying control. These are the shadowed men. The ones who don’t shout their pain or chase rebellion, but instead structure it. Order it. Use it.

Characters like Batman, Dexter Morgan, and Johan Liebert embody a kind of refined torment. They are high-functioning carriers of grief, trauma, or moral displacement. And while their moral alignments differ drastically, the pull is the same: men relate to their emotional containment. Their hyper-awareness. Their need to do something with all the inner weight they can’t speak aloud.

Batman: Discipline as redemption

Batman is the patron saint of controlled trauma. As Bruce Wayne, he’s a billionaire. But as Batman, he’s a walking monument to grief. His entire identity was forged in the split second his parents were murdered in front of him — a singular moment turned into a lifelong purpose.

He doesn’t cry about it. He builds. Trains. Plans. Hides behind shadows and fists.

“My pain became my reason.”

Men admire Batman not because he wears a cape, but because he refuses to let pain be random. He doesn’t want revenge. He wants control. Meaning. Direction. He turns loss into ritual.

This resonates with many who were never taught to feel, only to act. Men who take their chaos and disguise it as stoicism. Men who organise their pain into productivity because they don’t know what else to do with it.

Dexter Morgan: The killer with a code

Dexter isn’t just a serial killer — he’s a philosophical dilemma. Raised under the guidance of his adoptive father Harry, Dexter channels his compulsion to kill into a moral framework: only target other murderers.

What makes Dexter so compelling isn’t the murder — it’s the mask. His entire life is performance: socially competent, romantically engaged, professionally respected. But underneath, he’s a void. Or so he tells himself.

“I don’t feel anything. I fake it. That’s what people do, right?”

But of course, Dexter does feel. We see him struggle with love, family, loyalty. He just doesn’t trust those feelings. He was taught not to.

For many men, Dexter is relatable not because they share his darkness — but because they know the pressure of performance. Of living in a society that demands masks and codes. Of feeling like something is inherently wrong or broken inside — and building elaborate systems to hide it.

Johan Liebert: The mirrored abyss

The most unsettling “literally me” character is also the most beautiful: Johan Liebert, from Monster. He’s soft-spoken, refined, and devastatingly intelligent. But he is also empty — entirely capable of orchestrating death and destruction with a calm smile.

Unlike Batman or Dexter, Johan doesn’t chase justice or hold a code. He simply wants to see the world reflect the void he feels inside.

“There’s nothing special about me. I’m just an ordinary monster.”

Johan is the final evolution of emotional alienation — a man whose trauma has erased the boundary between self and silence. He is the question: what happens when you stare too long into the abyss — and the abyss becomes you?

And yet, men still whisper “literally me” under his image. Not out of admiration for his actions, but because they see the early signs of that void in themselves. The unshakable numbness. The dissociation. The haunting feeling that something is irreparably broken — and the fear of what might grow in that space.

What they all share

Why Men Say “Literally Me”

Pain without expression

These characters hurt — but they don’t announce it. They channel it. Structure it. That’s familiar to many men.

Purpose in control

They don’t rebel like Tyler. They refine. Their suffering doesn’t explode — it crystallises.Detachment as armor

Feeling too deeply can be a liability in a world that doesn’t allow men space for softness. These figures are what happens when you stop asking for space — and just build your own rules.Fear of becoming the monster

There’s a recurring fear in male identity: what if the thing that’s broken in me can’t be fixed? These characters live out that question — and offer both caution and catharsis.

The Culture That Built the Mirror

To understand the “literally me” phenomenon, you have to understand the landscape it rose from. This isn’t just about movie characters — it’s about the quiet cultural shifts that left many men emotionally starved, spiritually unmoored, and deeply alone.

These characters aren’t escapes from reality. They’re reflections of it — only sharper, more defined, more honest.

The Collapse of Clear Identity

The internet promised connection. What it delivered, for many, was surveillance, comparison, and echo chambers. Gen Z and Millennials are the first generations raised with endless connectivity — and increasing emotional disconnection.

Loneliness statistics have skyrocketed. More men report having zero close friends than ever before. They interact more with avatars than actual intimacy. Vulnerability, once something shared privately, now risks public ridicule or digital exploitation.

So they turn inward — and outward to characters who reflect that interior world. Theodore’s relationship with an AI isn’t absurd — it’s prophetic. Elliot’s monologue feels more honest than any Instagram story. Even Johan’s numb detachment mirrors the glazed-over scrolling of a man who hasn’t spoken truth in weeks.

The Performance of Masculinity

Modern masculinity is often a performance without a script. Say the right thing. Not too soft. Not too hard. Be emotional — but not needy. Be strong — but not toxic.

So what do men do with their genuine feelings? Many suppress them. Others channel them into hyper-stylised versions of control or chaos. “Literally me” characters are exaggerated models of that repression.

Batman doesn’t cry. He trains.

Elliot doesn’t hug. He hacks.

Tyler doesn’t talk. He punches.

It’s cathartic because it’s emotionally legible.

These characters give form to the feelings men are not allowed — or not equipped — to express. They take private fears and dress them in cinematic grandeur. The monster, the detective, the AI lover — all masks for something more universal: I don’t know who I’m supposed to be, and no one ever taught me how to ask.

Why This Isn’t Dangerous — If Engaged With Honestly

Critics argue that glorifying these characters leads to toxic masculinity, detachment, or nihilism. And yes, taken uncritically, that’s a risk. But most men aren’t idolising Tyler Durden because they want to build an anarchist army. They’re resonating with him because they too feel suffocated by a world that won’t let them scream.

The key is in how you relate. These characters don’t need to be copied. They need to be understood. They are mirrors, not blueprints. When engaged with thoughtfully, they become tools for self-awareness, not self-destruction.

Theodore can help a man realise he still has emotions buried under all that numbness. Dexter can help someone recognise the toll of constant masking. K shows that identity doesn’t need to be earned to be real.

This Is Not Just a Male Experience — But It’s a Male Language

Plenty of people across genders resonate with these characters. But for many men, they become an emotional dialect. A way to say “I feel this” without having to explain or soften it. Without having to be vulnerable in a world that hasn’t made room for that.

These characters speak the emotional language men were taught to repress: longing, guilt, emptiness, confusion, suppressed rage, and the aching desire to be understood without judgment.

So when a man sees a still from Her and retweets it with “literally me,” it’s not a joke. It’s a prayer.

What We Carry Home

Maybe it starts with a meme. A still image. A line from a film you haven’t seen in years. “Literally me,” someone writes, almost ironically. But the truth is, it’s not ironic at all.

What we’re really saying is: This character feels what I feel but cannot say. This character has been where I am, or where I fear I’ll go.

These characters — Theodore, K, Tyler, Elliot, Batman, Dexter, Johan — they are not idols. They are altars built from pieces of ourselves. They carry the weight of things we were never taught how to name.

When Fiction Speaks for Us

The stories we cling to aren’t just entertainment. They’re echoes. Permission slips. Translations of the feelings we’ve buried in silence. A man watching Blade Runner 2049 isn’t obsessed with the slow pacing or neon — he’s haunted by K’s quiet devastation when he realises the memory wasn’t his. He’s crushed by that mirror: what if the story I built around my worth isn’t even mine to hold?

When someone says “literally me,” they’re not always talking about plot or personality. They’re talking about emotional alignment. About watching someone break in the same rhythm they’ve been breaking in for years.

The Power of Silent Recognition

These stories do something we often don’t let real life do: they listen. They don’t interrupt. They don’t tell us to man up or move on. They just sit with us.

In that sense, they become a kind of emotional rehearsal. Before a man tells someone he’s hurting, maybe he tells himself he’s like Elliot. Before he admits he’s still in love with someone who left, maybe he replays Theodore’s quiet heartbreak again.

That’s not cowardice. That’s navigation. It’s emotional cartography. These characters map the terrain of grief, longing, alienation, and, most importantly, survival.

Survival Is the Point

None of these characters are “fine.” They’re not fixed. But they’re trying. And that’s what matters. Whether it’s K laying in the snow, Elliot finding fragments of himself, or Dexter holding his son and wondering if he can be anything other than what he is — what these stories give us isn’t perfection. It’s possibility.

They tell us: You are not beyond repair. Your fracture is not your final form. There is dignity in trying to understand yourself. There is nobility in choosing softness after a world that taught you only armour.

Literally Me, Actually Us

It’s tempting to think this is a niche subculture — men on Reddit or X or TikTok reposting brooding screenshots. But it’s bigger than that. These posts are signals. Beacons. Men saying: I see myself, and I hope someone else sees me too.

Every “literally me” post is a breadcrumb in the forest. An attempt to be known without explanation. Because explanation is hard when you’ve been taught to hide your feelings in utility, silence, or sarcasm.

What we’re seeing isn’t a meme. It’s a moment. A quiet revolution in emotional expression. And it doesn’t need to be loud to be real.

The Next Step: Owning the Narrative

The danger is not in identifying with these characters. The danger is in stopping there. If Tyler is your mirror, ask yourself what you’re ready to break. If Theodore feels like home, ask what kind of love you’re afraid to accept. If you see yourself in K, in Elliot, in Johan — ask what part of you you’ve never given a name.

“Literally me” is the start of a sentence.

Finish it.

This is what fiction does best. It holds space. It absorbs what we cannot say and reflects it back in language, color, and sound. It teaches without preaching. It reminds us that even our worst thoughts have been felt before — written into someone else’s arc, someone else’s pain, someone else’s attempt to find meaning in the dark.

So yes — he’s literally me. And that doesn’t make me weak. It makes me seen.

And that is how healing begins.

These characters are not destinations. They are mile markers. What matters most is who we become after seeing ourselves in their shadows.